Lost WWII map reunited with vet

Published 7:03 pm Thursday, July 7, 2011

POSING WITH THE MAP in front of the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum near Savannah are Lt. Earl B. Douglass, Jr., on the left, and Dr. John Vanzo.

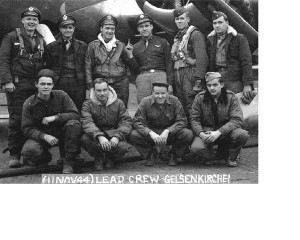

WARTIME PHOTO OF LEAD CREW for 303rd BG (H) Combat Mission No. 272, Nov. 11, 1944. Target: Buer Synthetic Oil Plant at Gelsenkirchen, Germany. Lt. Earl B. Douglass is kneeling at far right.

CLOSE-UP OF BOMBING MISSION MAP. The small swastikas drawn above the bomb symbol for Brux, Czechoslovakia, denote two German fighters claimed shot down by Douglass’ B-17 during the mission.

By JOHN VANZO

Special to The Post-Searchlight

“History Detectives” is one of the most popular television programs produced by the Public Broadcasting System. The show features historical researchers uncovering the unknown back-stories of various artifacts provided by private citizens.

Bainbridge College professor John Vanzo recently embarked on his own odyssey of historical research on a bombing mission map dating from World War II.

In the end, a heroic U.S. Air Force veteran was reunited with a long-lost souvenir of his service that he had not seen for 66 years.

Earl B. Douglass Jr., grew-up as a typical child of the Great Depression. Born on July 7, 1924, in the tiny rural town of Talbotton in west-central Georgia, Earl dreamed of bigger and better things. But war interrupted his ambitions for a college degree, and in 1942 at the tender age of 18, he entered the U.S. Army Air Corps for pilot training.

In late 1943, with newly-minted pilot’s wings and lieutenant’s bars gracing his uniform, Douglass was posted to the 303rd Bomb Group located in Molesworth, England. The 303rd Bomb Group, known collectively as “Hell’s Angels,” was one of the earliest American air units to be deployed for combat against Nazi Germany. Outfitted with approximately three dozen B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, the unit carried out some of the toughest and costliest bombing missions of the war.

On arrival at his new base, Douglass was assigned sleeping quarters in the officer’s billets. According to his roommate, Earl would be bunking in the bed once slept in by the famous movie star of “Gone with the Wind,” Clark Gable.

“They told me that I was going to sleep in Clark Gable’s bed. Capt. Gable had flown five missions with our group as a combat photographer, and now I was going to be sleeping in his bunk. Unfortunately, none of him rubbed off on me!” joked Douglass.

Douglass went on to fly 30 combat missions against the Germans, usually in the dangerous tail gun position of the B-17.

“The policy at that time was to split up a new pilot and his co-pilot for their initial five combat missions so they could gain experience from the ‘old hands’. While I was separated from my original flight crew, they were shot down and all killed. So, I became a sort of orphan within the Bomb Group,” recalls Douglass.

“My squadron operations officer ‘requested’ that I volunteer to serve in the tail gunner position because the Top Brass wanted a qualified pilot to be the eyes behind the mission commander’s head to make sure that all the planes in the group maintained proper formation. It was important for us to stay in a tight, carefully-designed flying formation to maximize our defensive firepower, and to keep all the bombs on target. So I flew as a ‘Tail Gunner-Observer’ in the lead aircraft on most of my missions. On other missions, I flew as co-pilot.”

Like most members of his generation, Douglass is extremely modest about his wartime service.

“Many of the missions I flew were ‘milk runs,’ that is, easy missions with little opposition. The really heavy fighting had taken place in ’43. By the time I got there, the Luftwaffe was basically already beaten and we had far fewer casualties.”

Despite Douglass’ modesty, the historical record shows he flew on many tough missions, with murderously heavy flak and sometimes swarms of attacking German fighters, including some of Hitler’s “Wonder Weapons” like the ME-262 jet and the ME-163 rocket interceptor. Even non-combat flights could be dangerous. On one flight, Douglass had to bail out of his B-17 because of a fire in the ball turret hydraulic system.

After 30 combat missions, Douglass’ tour of duty was over and he returned to the States.

“At that point in the war, the Air Corps required a flier to complete 35 missions before his tour of duty was over. But they credited me with a bonus of five extra missions because I had flown in the lead aircraft so often. Let me tell you, I was happy to accept those five extra missions and return home!”

While Douglass was stationed at Molesworth, he acquired a map of Central Europe and began to record on it his bombing missions.

“Just as a way to pass the time between missions, I got hold of an old map of Europe and began marking down the missions I flew. Nobody wanted the map because it was the wrong scale to be used for navigation, so I tacked it to the wall of the quarters that I shared with another officer. I used a cut-out stencil to draw the shape of a bomb on the margins of the map, and recorded the date and target city of each mission.

“In all the excitement and confusion of returning home after my tour of duty, I accidentally left the map on the wall when I packed up. For the next 60 years I really never gave it any thought. But then a few months ago a college professor left me a mysterious phone message telling me that he had tracked me down and wanted to return an old map to me. Then it all started coming back to me.”

Despite being an associate professor of political science, Dr. John Vanzo has had a life-long interest in military history. Always on the lookout for things to add to his collection of war relics, he attended a militaria auction held in Tallahassee, Fla., in March 2011.

“A map of central Europe with 30 bombing missions drawn on it was listed in the auction catalog. Initially it did not interest me. However, when I actually saw the map, it ‘spoke’ to me,” Vanzo said. “On pure impulse, I placed a bid and won the auction. I brought the map to work, intending to hang it on my office wall.”

Sitting at his desk, Vanzo’s attention kept being drawn to the bomb missions listed on the map. Curiosity eventually grew into an irresistible desire to identify the unit that had carried out those missions.

After a few days of library and Internet research, Vanzo determined that the only unit that could have flown those exact missions was the 303rd Bombardment Group (Heavy), a B-17 outfit stationed in England during the war. That further piqued Vanzo’s interest because his late stepfather Col. Frank Cappelletti had flown in B-17s against Japan during the war.

An Internet website devoted to the 303rd listed all missions flown by the group, including the specific aircraft and crews that flew each mission. Vanzo tried to identify which particular airplane had flown the map missions, but to his disappointment, he found this was impossible. According to the website’s historian, Gary L. Moncur, crews did not fly one individual aircraft, but rather rotated between several aircraft.

Even though there was no one plane that flew the 30 missions, it was theoretically possible to identify the individual crewman who flew the map missions. But this would entail again going through the 30 mission lists, each with 300-350 different men, to find the one man who was common to all the missions. With dread, Vanzo started on that Herculean task. But Moncur came to his rescue. Using some computer spreadsheet wizardry, he found the one man who flew the map’s missions: Lt. Earl B. Douglass.

The website’s contact information for Douglass was long out of date, but after an afternoon of Google searching, Vanzo found an address and phone number for an Earl B. Douglass Jr.

“I assumed that the veteran had passed away, and that his son, Earl Junior, had sold his father’s estate to the auction company,” said Vanzo. “To my shock, I received an email from Earl B. Douglass Jr. saying that he was in fact the veteran himself. He congratulated me on my research skills and said he had not seen the map since the days it hung in his barracks room in England during the war!”

Douglass and Vanzo arranged to rendezvous April 23 at the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum near Savannah. Four of Douglass’ friends would fly him in a private plane from his winter home in St. Augustine, Fla., to tour the new B-17 exhibit at the museum, and to see the long-lost map.

Vanzo said that Douglass turned out to be an incredibly vivacious, sharp-witted and humorous gentleman, despite his 86 years of life. Douglass told Vanzo that after the war he attended classes at the University of Georgia and embarked on a long career as a transatlantic pilot for Pan American Airlines. Douglass was incredulous how the map, which someone had thought highly enough to frame, had found its way back to him.

Over lunch, Douglass very generously insisted that the map was Vanzo’s to keep, and that the real story was the professor’s historical research.

Vanzo, on the other hand, insisted that the map was Douglass’, and that the real story was the veteran’s heroic service to our nation.

In the end, they agreed that copies of the map would be made for each of them, and that the original would be donated to the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum for permanent display. Museum President and CEO Henry Skipper has accepted the map as a “treasured addition” to the collection.

“I am happy to donate the map to the museum,” said Vanzo. “The money I paid for the map is inconsequential to me; what is priceless was the opportunity to meet and talk with such a stellar example of this ‘Greatest Generation’ of Americans, who willingly risked and sacrificed so much in order to preserve the comforts and freedoms we all enjoy today. The map belongs in a museum for future generations of Americans to see … lest we forget.”